Seeking Ariadne's Thread: Eric Fuller on the Art of Making Puzzles

Source: Seeking Ariadne's Thread

Author: Saul Symonds

For over a decade, Eric Fuller has been crafting some of the most original and coveted wooden interlocking puzzles and puzzle boxes. His own designs as well as those from designers around the world are available through his online store Cubic Dissection. Many people make or design puzzles as a hobby, but Eric belongs to an elite group that succeeds in making puzzles for a living.

Eric’s enthusiasm is evident everywhere on his website. Not content to merely list the dimensions, woods, level of difficulty and other information relevant to the puzzles he is selling, he provides customers with an introduction to each puzzle conveying, for example, his excitement over a new design or an intensely complex production process.

His perfectionist personality as a craftsman can also be seen in other aspects of the finished puzzles. Two examples are Markus Götz’s Framework II in which he instigated a process that saw the original design modified from having at least 15 solutions to having only one and Goh Pit Khiam’s Tern Key in which he added steel pegs to the acrylic keys as he found manipulating the acrylic directly with fingers a little uncomfortable.

Between a busy month in his workshop producing a new batch of mechanical puzzles, Eric found time to chat about what lies behind his puzzle making process.

Saul Symonds: The first puzzle design by you listed on Cubic Dissection is a six piece packing problem (Pack 6) and the next puzzle is a cube you made with your old roommate (Jason’s Cube). Apart from remaking Pack 6 some years later you have moved solely into the design of puzzle boxes. At what point did your interests crystallise and move away from the earlier packing-type puzzles?

Eric Fuller: Honestly I’m not a very good interlocking or packing puzzle designer. There was nothing particularly interesting or groundbreaking about either design. I think Pack 6 is a really fun beginner puzzle, but it’s nothing that hasn’t been around forever.

I feel very constrained designing interlocking and packing puzzles. The ones that get really big become cluttered and verge on unsolvable. So it’s tough to come up with an elegant design since you’re generally limited to a reasonable number of units. Put it this way: Coffin’s Three Piece Pyramid does more with ten cubes than most puzzles do with ten or twenty times the space.

Designing puzzle boxes comes much more naturally to me. I feel free to let my mind roam and come up with really tricky stuff. I’m not locked into a 4×4 or 6×6 or whatever configuration. Also I can use joinery in clever ways, which is very satisfying as a craftsman. So, to answer your question, it was very early for me. That said, there are many excellent designers these days that DO make interesting puzzles within those constraints, and they have my admiration. Also my gratitude for allowing me to make their designs.

SS: How has making puzzles from other designers shaped your own puzzle designs?

EF: It hasn’t to my knowledge. Probably because I focus my design efforts on boxes, and only make non-box puzzles from other designers. I find very little overlap between them.

SS: How do you choose which puzzles you want to make?

EF: Tough to say. Something has to grab me, either the final shape or the overall concept or even a tricky series of moves. I’ve passed on some designs and later regretted it when I saw another craftsman make the puzzle. Ternary Burr falls under that umbrella. Because I do this as a living, I do have to consider how much time a puzzle will take vs. how much I can sell it for. Some designs are great but just too complicated to do right – I’d have to charge more than I think people would be willing to pay. I’ll pass on a design before I’ll skimp on quality to meet a price point.

SS: From time to time you remake a puzzle that you have already made. Sometimes you note that there have been significant improvements (the addition of a puzzle box to Die in Prison) but with others it just seems you wanted to make it again, such as Oskar’s Paperclips or Stewart Coffin’s Half Hour Puzzle. Given the fact that you often state after completing a puzzle that you will never ever make that puzzle again what are the factors that cause you to do so for these particular puzzles?

EF: Generally it’s puzzles which are a lot of fun and that I’m just enthusiastic about. Oskar’s Paperclips and Matchboxes are a good example – I think they’re just so unique and clever that I’m always happy making them. While I try to only make interesting puzzles, some simply stand out, at least in my eyes. Another factor is my customers. While I don’t take requests per se, if enough people ask that I remake a certain design it holds weight. Not that I keep a tally; it’s a very subjective thing.

SS: In your description of Stewart Coffin’s Lock Nut you note that only 14 of the 40 ended up for sale due to the difficulty of cutting the angles. What is the most difficult puzzle you have made to date?

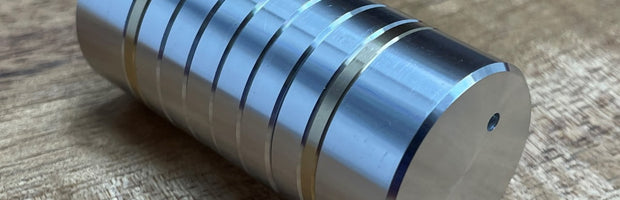

EF: Definitely the puzzle boxes are more difficult, which is why I have to charge more for them. Consider the 51 Pound Box: I had to mill custom aluminium latches; do complex glue ups with metal reinforcing tabs; tricky mitered shoulder joinery; purchase, handle and install absurdly powerful magnets; work with veneer and inlay; etc. There’s a LOT that goes into even the simplest looking box. Some interlocking puzzles can have tricky elements but in the end you’re mostly just making notches, shoulders or crosscuts. Once you get the jig down, everything else is attention to detail in the execution. That said I’m tackling some Wayne Daniels designs next year, so come back and ask me then.

SS: Are there puzzles that you have put off making because they are too hard? It seems like you constantly push your woodworking skills with puzzles that are increasingly difficult to make.

EF: I can’t think of any I’ve put off due to difficulty. Mainly it’s economics that put a design off … if it’s hard, it’s going to take longer and I have to charge more for it. So I try to develop my skills in a measured way. If I didn’t and jumped in the deep end, I’d either go broke or make my customers angry by overcharging. By pushing myself gradually I can spread out the cost of my continuing education. By making a couple “safe” designs along with one which is a reach for me skill wise I can charge a bit less for the reach one even though it cost me more time because I was so efficient with the safe designs.

SS: The first time you made Half Hour Puzzle in 2004 you offered it in a choice of seven different exotic hardwoods, but each particular puzzle used the same wood for all six pieces. The second time you made it in 2013 each piece was made from a distinctly different type of wood. This seems to illustrate a general trend in your choice of woods with a predilection these days for combining several different types into a single puzzle. How has your choice of woods within a single puzzle changed over time?

EF: I generally prefer more muted colors. Contrast is always good, but my personal preference for puzzles that I will put on my collection shelf is that there be only one or two separate colors or tones. My customers however seem to really love the opposite; whenever I make a puzzle with all different wood types it seems to sell out more quickly than those with only a couple or even a single wood type. So in this case I’m discarding my personal preference to cater to the market. Since I get to make whatever I want it seems like a fair tradeoff!

SS: Do you ever consult the designer on your choice of wood?

EF: It’s very unusual that I do. Normally I have to have complete freedom to interpret a design as I will before I agree to make it. Generally designers seem to be ok with this. Few of them are woodworkers, and there are sometimes technical reasons to use one wood over another. Occasionally I will have to tweak a design to make it stronger or more production friendly.

SS: And how does the shape/design/solve of a puzzles affect the choice of wood?

EF: Some wood is very dense and is therefore more difficult to mill deep notches into. So I would avoid using that for a puzzle I knew I would need to make a notch that is deeper than say the notch width. Some woods glue much better than others, so if a joint has less exposure I would avoid using oilier woods that glue poorly. Some are more stable during the milling process and will therefore turn out more accurately. It’s just something you learn with experience over time. To this day I sometimes regret choosing certain woods for certain projects, but in the end I manage to make things work out.

SS: How do you decide the size of the finished puzzle, the thickness of the wood, and so on. Some puzzles you have made have been interpreted by other craftsman with different results, as you pointed out when described your choices for Oskar’s Matchboxes.

EF: Of course the design of a puzzle dictates how many units it is as a whole, and therefore you have constraints there. That said I generally try to keep puzzles between say 2.25” and 4” in size. I find it’s just the sweet spot for collectors. You want them to be big enough that they are easily manipulated, but small enough that they don’t take up an inordinate amount of space on the shelf. Also I feel that smaller puzzles are more difficult to make and thus the size can be somewhat a hallmark of quality. Consider this; any error you make on a puzzle is halved on a scale of relative tolerance if you double the size of the puzzle. It’s MUCH easier to work with 1” square stock than it is with say .625”. When I started I worked with roughly one inch sticks because that’s all I could find at the hardware store. Now of course I mill all my stock to custom size, so I can make it any way I want. I’ve to some extent standardized a lot of puzzles at around .75” stock and therefore many times .375” units.

SS: It would seem that for the puzzles you build you often would not have the chance to enjoy the process of discovering the solution, so what type of puzzles do you play with in your spare time?

EF: Well, the assumption that because I make a puzzle I automatically know how to solve it is incorrect. When I make a puzzle I have a piece set that I am manufacturing … so long as I stick to the tolerances, I can be assured that the puzzle will work the way it is meant to. So in the end I have piles of pieces … but still no idea how they go together. That’s when I get to solve it! While I suppose sometimes making the pieces provides an insight into how the puzzle operates as a whole, most times it does not. So in the end I solve it just like you. Unless I need to hurry up and ship it, in which case I cheat with the directions. The solving occurs at work though. So I guess I get paid to solve them … pretty cool.

As far as my spare time, mostly I am doing sports or socialising or other non-puzzle activities. When you spend all day every day working on puzzles it does sometimes become work. However I always enjoy a new puzzle box. They were my first love and will always be my favorite I suspect.

SS: You wear many hats in the puzzle world: designing, making, solving and selling. Which do you enjoy the most?

EF: I like designing and solving them the most … followed by making then much much behind that is selling. Frankly the business side of this is very boring, and I’m always doing things such as accounting and taxes at the last minute. I’m much better at making puzzles than I am at running a business.

One choice I was not given is the people. I love the people associated with this trade more than anything. They are the most open, honest, fun, generous and cool people you will find anywhere. I have met some lifelong friends and shared so many good times with them. I’m forever grateful that they have supported me all these years … I think of my customers as patrons really, and THEY are what I enjoy the most.